Learning to Do Historical Research: Sources

The Interview Dance

When to lead, when to follow

Cathy DeShano

Kevin Gibbons

Trish O'Kane

“I don't mind being interviewed any more than I mind Viennese waltzing - that is, my response will depend on the agility and grace and attitude and intelligence of the other person. Some do it well, some clumsily, some step on your toes by accident, and some aim for them.”

---Margaret Atwood

Introduction

Some of the most vivid and interesting histories come directly from the narratives of the people who were actually there. In this Information Age we have become accustomed to finding information with one click of a mouse instead of searching out more hidden, subtle, and textured data. Direct or recorded interviews can often provide this texture; don’t overlook them as valuable sources.

In this section we will give you the tools you need to use the oldest source of data and information: the oral history. While the options for recorded interviews may seem limitless, and the process of interviewing may seem daunting, we encourage you to try it. People's stories can contain gems of information, insight, and wisdom, if we can only find the time to stop and listen.

Table of Contents

Should I conduct an interview or use the archives?

There are thousands of oral histories that exist that could provide rich material for your research. If you're interested in learning about existing oral histories, you may want to check with your local library or historical society to ask about oral histories they may have. State historical societies and colleges or universities also may be valuable resources for existing oral histories. You also can find oral histories on the Internet by searching "oral history." Although you won't be able to gather details, such as people's facial expressions, when you use oral histories conducted by other individuals, these still are valuable resources. Links to some of our favorite oral history sites are included in the Interesting Links and Sources section.

If you’re trying to determine whether to conduct interviews to glean information from people or to use existing oral histories, you’ll want to examine whether there are people to talk with who can answer your questions. Think about how important it is to your research to have first-person perspectives and who can give you these. Your best informants may be people who have been interviewed by others, or you may need to conduct new interviews.

Return to Top of Page

Imagine being able to listen to Cesar Chavez talk about the struggle for migrant workers’ rights or learning about cotton picking during the Great Depression. Oral histories can be as engaging as a great conversation over a good cup of coffee. They allow you to learn about people, moments, experiences, and events that you may not have first-hand access to otherwise.

Once you’ve found the archives where these treasures are located, you’ll find that the interviews vary widely in topic, length, format, and formality. Some archives may have interviews that are recorded on tapes, so you’ll need to visit the institution to listen to the recordings. Others may have transferred all or parts of their oral history collection to digital format, so you may be able to listen to them from your preferred location. Call or email before visiting any institutions so you can schedule an appointment to learn more about the various features of oral history collections.

When you email staff at oral history collections, ask them the protocols for using oral histories: if you need to go into the archive to listen, what rules do you need to follow? Tell them in the email what you are researching and ask for suggestions. For example, if you’re writing a paper about the history of arboretums, archival staff often can point you toward valuable oral histories that address that specific topic. Here’s one example: if you are researching the arboretum operated by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, you’ll learn that individuals began pushing for this arboretum during the 1920s, just before the Great Depression. When Wall Street crashed, the main backer of this arboretum project committed suicide and the project sat for several years. You’ll learn in this interview how the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl eventually spurred the building of the arboretum. Listen to a few minutes from this hidden treasure that lies buried in UW-Madison’s Oral History Archive: William Jordan III talking about the UW-Madison Arboretum

This interview excerpt shows how environmental history is inextricably linked to economic and social history. As you listened to William Jordan’s voice, what questions came to mind? These are the types of questions you’ll want to focus on in your research. These are the questions that will help you dig deeper. This excerpt focuses on arboretum history but interviewee William Jordan was also a founder of the discipline of restoration ecology. Not only did he coin the term, he founded the discipline’s first academic journal and wrote a seminal text on the subject. But you won’t find this out unless you go into the archives, listen to the entire interview, and dig through Jordan’s biographical file.

To use existing oral histories like the one you just listened to, you need to know how to take good notes so visit our Note Taking section. Some of the basic items to jot down include the following:

- Person interviewed

- Date the person was interviewed, when available

- Topic about which he or she was queried

- Length she was interviewed and whether the interview was conducted during multiple sessions

- Specific locations, events, names, dates, or other such information the individual touched upon

- Verify names and clarify individuals

Interviews vary greatly in the information shared. You may take pages of notes during one interview yet just a few paragraphs from another interview about the same topic. Some people interviewed focus specifically on the topic at hand, while others meander all over the place. Often there is no way to know ahead of time what interviews will have the best information for your paper. So see your archival visit as a grazing adventure—buried in the crabgrass you may find tender, juicy tidbits of tasty clover but you’ll have to roam around a bit.

As you listen to interviews, don’t feel obligated to take notes on every piece of interesting information since this could add up to pages of extraneous details that overwhelm you. When you come across ideas that seem appropriate, note the approximate time they occur during the interview – the 5-minute mark, for example – and the estimated length – for 10 minutes. This makes it much easier to return to the ideas you need.

When you use existing oral histories, you don’t have the opportunity to ask the individual follow-up questions. If there are gaps in pieces of information or the individual touches on some, but not all, of your research topics, fill in those gaps by using additional oral histories and other research sources.

Try This...

Let’s go on a little fishing expedition. Go to UW-Madison's Oral History Project at http://archives.library.wisc.edu/oral-history/interviews.html . On their main page hit “Oral History Program,” then “Oral History Interviews.” You can browse the interviews in several ways—by a person’s name, an interview series, or a university department. We have no names of people, yet, or particular subjects in mind other than something environmental so we hit “university department.” The departments are listed alphabetically and because we’re lazy, we hit “A.” The first university department listed that has anything to do with the environment is “Agricultural Economics.” A list of professors who worked in this field appears. The second one is named Raymond Penn, a nice literary name, so we hit him. A short bio appears. In 1981, one Douglas Yanggen interviewed Dr. Penn for 2.5 hours. Penn told Yanggen about the development of water law in Wisconsin before 1949, about dam building, and about cranberry growers, among other things. There are over 1,000 interviews in the archive and most have not been transcribed—the Penn interview is one of them. So we email the archives and make an appointment to go and listen to him.

Sign Pointing to UW-Madison's Archives on 4th Floor of Steenbock Library

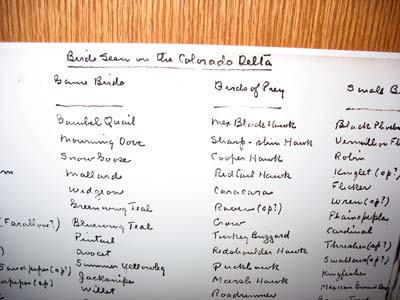

When you enter the UW-Madison Oral History Archives, you are stepping into an intellectual archeological dig. Taped to the main desk on the left, sits a photograph of a page from Aldo Leopold’s field diary in 1922, where he jotted down lists of birds.

Birds Seen in the Colorado Delta, 1922

Photo Copy from the UW-Madison Archives of Aldo Leopold’s Field Diary from 1922

At this main desk, we ask for the “biographical file” on Penn. The materials in the biographical files are not online and we want to sniff around in his life before we actually hear his voice.

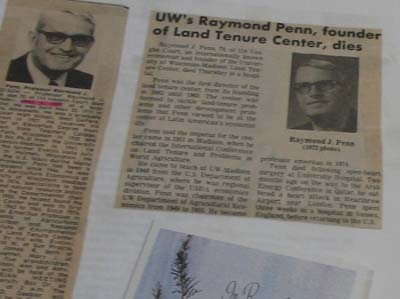

From underneath the pile of forty-year-old typed university press releases, a man emerges. He’s wearing Clark Kent eyeglasses. His handwriting in pencil is still neat and clear in the “Faculty Information Sheet” that he filled out decades ago, when his sons were just three and five. Before our very eyes, he morphs from young father and new faculty member into major state player on water legislation and world expert on land reform. Water issues today in the Great Lakes region are at the top of the environmental agenda. Did he foresee the problems we now face? Wisconsin today is the nation’s number one cranberry producer. How much did he have to do with that? Penn was also very concerned about the need for zoning laws in the 1950s. At that time, the nation was undergoing a major wave of suburbanization, as marshes and wetlands were filled in to build cookie cutter subdivisions. In a yellowed Madison Capital Times article dated January 20, 1958, he expressed these concerns to a reporter: “…ordinances for zoning can prevent landowners from either knowingly or unwittingly exposing themselves and their property to physical hazards. An obvious example is restricting a river’s flood plain to uses which will not involve substantial loss in the event of a flood…”

Newspaper Clippings from the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives about Raymond Penn from 1958 and 1982

What would Raymond Penn have to say today about the over 1,400 dead in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina and current debates over rebuilding along the Gulf Coast and the banks of the Mississippi River? We’d love to ask him, but we can’t. Buried in the file near the bottom is a small remembrance card with a single bluebird on it. Psalm 23, “The Lord is my shepherd” is inside. Penn died on May 6, 1982, at the age of 70. The somber university press release informs us that he fell ill during a work trip to the Middle East, and then died of complications following open-heart surgery. We smell the small, modest remembrance card. There is the slightest trace of lilac perfume still clinging to it. It’s time to put on those earphones and sit for an hour with Raymond Penn.

Return to Top of Page

Taking your own oral history can be a fascinating experience that can speak novel more than just reading about the story or someone else's summary. Here we have outlined some tips that will help you go through the interview process from preparing for the interview to writing it up.

Topic 1: Preparing for the Interview

Before you begin interviewing people, you’ll want to consider why you’re conducting the interviews. Examine how these interviews will help you develop a paper that focuses on a particular theme.

Student Taking Notes from Materials at the Archives

You may be doing these for a course assignment for which you’ve been given clear guidelines about the types of topics you can explore. If so, this will limit the people you’ll want to interview.

You may be given broad latitude in identifying a topic. If so, you’ll want to consider how the topic you choose contributes to public knowledge and identify people or oral histories that will aid your research.

All people have particular points of views about people, experiences, and cultures, for example. Before you begin your research and the interviewing process, consider the following:

Examine how your biases could influence your research experience and interviewing. Think about how your gender, cultural upbringing, age, racial background, and political views affect the way that you perceive people. For example, how might someone’s size affect how you relate with them during the interview process? Think about how differently you interact with someone whose politics are very different from yours. Your biases are so important! Get to know them. Here’s a tool to help you: www.tolerance.org/hidden_bias/index.html.

Gathering background information

Good interviewers prepare by researching the topic beforehand. You don’t need to know everything about the topic, but it’s important to have a solid grasp on significant events or themes so that you can ask intelligent questions. This shows people that you care about their experiences and what they’ll be telling you. It’s a way to build rapport.

There are a number of ways to gather background information about your topic. For a more comprehensive guide on searching, please visit this website's searching page. We suggest the New York Times archives and Lexis-Nexis to research events, issues, and people. You may want to conduct a pre-interview with people to gather basic facts and for some of the following reasons:

This helps both of you relax.

It also gives the individual a chance to sign a release form.

During a pre-interview, you can find out whether the person will be comfortable with a tape recorder or video camera. If they aren’t, you should plan to take notes only by hand.

Planning Questions

There are several different types of interviews, ranging from highly-structured—where you ask the same exact list of questions to every person—to totally unstructured. We suggest you use the semi-structured interview which falls in the middle of that range. In this type of interview, you’ll want to have some ideas for questions before beginning, but you should also listen closely to the person to ask follow-up questions. The semi-structured interview does the following:

- Gives you a general roadmap for an interview.

- Allows you to move on to your next question if there are long stretches of silence.

- Can give you a richer picture of a person's life because you ask follow-up questions based on the individual's unique experiences.

For each interview you’ll want to get the following life history information, at a minimum, for yourself and for other scholars who can use the data:

- Name

- Email

- Address

- Telephone Number

- Birth Date

- Birth Place

Keep in mind…

Interviews can be exhausting, so you may not get to all the questions you have during one interview. Many people get tired after about an hour. We suggest you work out an agreement about time limits with the person even before the interview starts. You may need to meet with the person multiple times for an oral history.

How to choose people for interviews

Your topic guides this answer. If you’re looking at the contract negotiations between farmworkers and vineyards in California during the 1960s, for example, you’ll want to talk with those who were directly involved, such as workers, owners, managers.

You also may want to consider less obvious resources, such as people who’ve lived in the area many years, journalists, or lawyers. Newspapers also can be valuable sources for ideas about whom to interview: look for people quoted as experts on your subject. Again, some of this will depend on your questions and how you think each of these people can contribute to your research project.

Begin by interviewing people who are passionate about the topic and willing to share their knowledge with you.

Informed participants

Once you have an idea of the types of people you’ll want to interview, you may need to create a consent form that participants will sign before the interview is conducted. If you're a college student, talk with your instructor about whether your institution has an Institutional Review Board (IRB) that must approve any interviews. The consent form should do the following:

- Make it clear that the individual can opt out at any time. Click here for an example of a consent form: Sample Consent Form.

- Include what, if anything, you will share with the participants about the final paper, such as their comments or the entire paper.

Topic 2: Building a Bridge

Your professor asks you to do an interview. This is not an email interview or an instant messaging exchange, but a physical encounter where you must sit with a stranger and ask questions for at least an hour. You are slightly terrified.

Fear is good. Your interviewee will sense that fear and probably feel sorry for you, and the sorrier they feel, the more readily they may talk. But before you enter that office or home, you have work to do. Show your respect for this person by becoming an expert on your topic (see "Gathering Background Information" above). As you do this research, pay special attention to any connection you can make during the interview since it's a good way to begin. For example, maybe they were born in the same small town as your grandmother. Maybe they are a golf freak and your father loves golf. People usually love to talk about family connections so that is an easy place to start.

When you schedule the interview, make sure that you will have that person's undivided attention for at least an hour. You do not want to interview people while they are multi-tasking or between patients, for example. If you can get that person to take you on a long drive or a long walk, that is another good way to interview someone, especially for an environmental history paper. Ask your interviewee to walk you through that park you’re writing about, or through the woods, or around that wetland restoration project.

Student with Audio Recorder

Arrive early and dress appropriately. Always dress respectfully and professionally, whether in a garbage dump or a Wall Street firm.

Don’t forget your tape recorder but do not turn it on until you have completed the next step of building a bridge.

You have approximately four minutes to establish rapport and build a bridge to this stranger, according to communications experts. If you did not find a connection during preliminary research, you have some fast work to do when you walk in the door. Make immediate eye contact, shake their hand firmly, state your name clearly, and as they walk back to their seat, scan the desk and walls for photographs, diplomas, plaques, and artwork. These are your historical artifacts--documents that tell you more about this person. Find an adorable grandbaby photo, a cute dog photo, or a diploma from a university that your grandfather also attended. Keep that notebook shut and tape recorder off. Settle into your seat and start building a bridge by talking about a photograph:

- Ask the dog's name. How old is it? What a coincidence--your family also has an ancient golden retriever with hip dysplasia.

- If the person keeps rambling about their family or a village in Mexico where they bought a wall hanging you admire, let them ramble.

- Smile. As you pull out your question list, tell them that this is your very first interview (if it is). Ask for their patience.

Topic 3: Recording and Jotting

Should I record or not?

If your purpose is to preserve the oral history, then you definitely should. Record the interview (digitally if possible) and ask your local librarians if they are interested in archiving the interview.

If you plan on developing a paper on a particular topic, like a newspaper article or ethnography, then having the recording is still important to draw out quotes or confirm what the person said.

Bear in mind that going through a recording, especially if you are doing a full transcription, requires a lot of time. An hour-long interview may take three to five hours to transcribe so adjust your workload accordingly.

"Jotting" is the act of taking down quick notes in a notebook when you are in the field but have little time to craft full-length thoughts. They are often done in fragments and can be difficult to understand. But later, you can synthesize them into more coherent thoughts and complete sentences in your "field notes.”

You can either jot things down while the person is talking or, if it does not seem appropriate to take notes during the interview, you can put your thoughts down quickly after the conversation is over. Then you’ll have more details available when you write-up your interview.

When it comes to jotting, nothing is too much. You can filter the important aspects out during the process of writing your field notes, so jotting is a process of getting every detail that you can muster out of your brain. Consider the following ideas when jotting:

- Do not try to use complete sentences for everything. Write down just enough to assure that you will understand the information in the future. Your field notes are your opportunity to make your jottings more cohesive.

- While you should jot, try to make as much eye contact with the interviewee as possible. It can be unnerving to speak to someone who is busy scribbling away. Try to find a balance between getting down as much information as possible and having a comfortable conversation.

- Talk a bit about the setting and the details leading up to the interview. It might be interesting to use for a story leading up to your history.

- Describe the interviewee in detail.

- Flag the interesting quotes by circling them or putting a star beside them.

- Where does he or she live? What does that city, home, apartment, etc. say about that person?

- What did he or she describe that piqued your interest?

- Throw in your opinions. These first impressions will be useful when you do your field notes and write-up the interview.

Topic 4: The Interview Itself

Listen. This next hour should be a conversation not an interrogation. Ask a few questions on your list, but make sure that you listen to what your interviewee is saying. Go into the interview with an open mind, not a research paper outline in your head that you are trying to fill in. The person says something surprising, so you ask:

- How did that happen? Could you describe that day/moment/event in more detail?

- When exactly did you realize this?

- What did you do next?

- What did it look/smell/feel like?

- How did you feel?

These are follow-up questions -- they come from the story your interviewee is telling, not the story outline in your head. Remember to listen to the individual. Don't be afraid if the interviewee tells you a completely unexpected story. You may end up with a far more interesting paper than you envisioned.

Silence is golden. When you ask a question, be quiet afterwards. Do not be afraid of long silences, especially if the person is talking about difficult subjects. Do not try to fill in the spaces to make them feel comfortable. Sit with the discomfort. Let them tell the story at their own pace and you will get juicier details.

Save the toughest questions for later in the interview. You've built your bridge; your interviewee is talking easily about subjects they like. Now it's time for hard questions. If they do not want to answer, back off and return to an easy subject. Try again before the interview is over. Rephrase the question so it is non-threatening. Tell them that you did not understand something they said. Ask them to explain it to you again.

When the interview is over, it may have just begun. Your hour is up. Your interviewee looks tired. You shut the notebook, turn off the tape recorder, and prepare to leave. When your interviewee hears that tape recorder click off, they relax. So pause before you get out of that chair. Ask them:

- Have I forgotten to ask you anything important?

- Is there anything that you would like to ask me?

Sit. Be quiet. If they start saying something really important, quietly pull out that notebook and start scribbling. When they say the most emotional things, stop scribbling. Just sit and look them in the eyes. As soon as they start rambling about something else, scribble down the juicy stuff. Don't worry about getting it perfect. You'll fix those quotes when you get out to your car.

Now the interview is over. You are sitting in your car in the parking lot or on the bus, infinitely relieved. But the job is not done. Before you drive anywhere, take out your pen, go over the key quotes, and make sure you've got them right. Jot down all the ideas that pop into your head. Scribble down every detail you can remember about that person and environment. This is your chance to get down all the information while it is fresh in your mind.

Topic 5: From Recording to Field Notes

Before you do anything else, label your tape or digital file. Two examples:

Tape: “James Monroe, September 29, 2008, Tape 1 of 2”

Audio File: “JMonroe_2008-09-29.mp3”

Try to do the work of indexing and writing field notes as soon as you possibly can after your interview, before the meanings and significance of details escape you.

Example of Field Notes from an Interview

Indexing is an important method for journalists and oral historians. To index the interview, listen to the tape or digital file and record the major topics of conversation in the order that they come up during the interview. Then record the times that these topics appear on the tape or digital file. Include notes and opinions whenever anything comes to mind. Indexing allows you or someone else consulting your recording to quickly find any points of interest.

Field notes should not necessarily be EVERYTHING from your jottings or the recordings. Read through them and do not be afraid to filter. Form complete sentences. Throw in your opinions while they are in your mind and put in style suggestions to remind yourself of some ideas.

The point is to synthesize your jottings to create a document that is easy to read, organized (to a certain extent) and that reflects pretty much everything that was said in the interview.

Completing the Interview Process

Ask yourself if the interviews complement/supplement one another. Does each contribute to the whole project? You may not need to include those that don’t. Save all your notes from interviews, even those that you think you may not use for this project. You may need to refer these later in the research process.

Review the agreements that you had with participants. Ask whether your final project reflects the nature of these agreements. If you’ve used their information in ways not expressed in the agreement, you may need to reevaluate this and go back to the individuals to explain differences.

Send thank-you notes to those who participated. Interviews take a lot of time and can be exhausting. It’s important to show your appreciation.

Type up a full transcript from your interview to analyze and fact-check. In a few days, when you have a clearer head, read the transcript straight through and ask the following questions:

- Is there anything that sounds strange or unbelievable? Could your interviewee have been exaggerating or lying?

- If you are unsure of something, call the person to check it, verify the information with another source, or do not use it at all.

- Check all dates, numbers, and place-names. You may be able to check dates of important events on-line or you can consult the archives of the local newspaper. Your public library is also a good place for fact-checking. Ask librarians for help as they may know of books or documents to help you fact-check.

- If your interviewee made contentious statements about another person and you want to use those quotes, get the other side of the story first. Remember that in the web world, anything you post on-line is considered published; if you publish something libelous about someone else, you might get sued.

Topic 7: Writing the Interview Up

There is no one way to write an article or oral history. If there were, writing would be easier, but reading would be pretty boring!

There are a few important points to consider when writing up interviews:

- Make sure your quotes are exactly what the interviewee said. If you are paraphrasing, do not use quotes around the statement.

- Always consider how you are portraying people. Show the interviewee respect. You don't have to agree with what they say, but ask yourself, “Would they be offended if I wrote this about them?”

- It’s always helpful for the final write-up to take down a list of compelling quotes from the interview, which can provide inspiration if you hit writer's block.

- What did he or she NOT mention? What does that say about his or her perspective?

- If you are taking information from an historical interview, make sure to cite the source, date, and location of the interview.

- Don’t just use the person’s words. Don’t be afraid to discuss the setting, describe the person in detail, or share interesting moments. One of the main reasons that we write about interviews is to bring our readers into the interesting conversation that they could not be a part of.

Return to Top of Page

- LEARN FROM YOUR MISTAKES: Good interviewing skills will serve you in any people-oriented career. To improve these skills, type up a full transcription of this first interview. Use a highlighter to highlight anything interesting that the person said and that you forgot to follow-up on. Study their responses to your questions. Critically analyze the transcript. What holes are there in the story that they gave you? What did you forget to ask? Think about what you will do differently the next time. Compare your interviewing style to two of the greatest interviewers of all time--Studs Terkel or Oriana Fallaci (see online resources below). What would they have asked this person? Perhaps you can do a shorter follow-up interview to fill in the information gaps.

- INTERVIEW A FRIEND OR FAMILY MEMBER: It is important to practice these methods and improve your skills. Interview your friend or a parent for at least 20 minutes, using your recorder. Take down jottings while trying to make the interviewee feel comfortable and attended to. Listen and index the recording and develop field notes that can be used to write a respectable article.

- VISIT THE LIBRARY AND LIBRARIAN: To see how the experts index, visit your local library and ask the librarian to show you some indexed interviews. Choose an interview, read the index, and listen to a section on a topic that interests you. While doing this, make sure to note how the interviewer indexed. What about it is effective and what needs clarification? How would you index the interview?

Return to Top of Page

Dos

- Do search for an archived oral history for your topic.

- Do talk to a librarian working in the oral history archives and get your hands dirty.

- Do treat your interviewee with respect by showing up on time and being well prepared.

- Do come with a flexible list of questions and pieces of information that you do not want to leave the interview without.

- Do listen more than you speak.

- Do take detailed notes during and after the interview.

- Do transcribe your interviews.

- Do index your interviews with detailed notes of the date and person interviewed so that you will not forget these details when you get to your writeup.

Don’ts

- Don’t undertake an oral history without searching through the archives.

- Don’t come to an interview unprepared.

- Don’t just read off your list of questions without engaging in conversation.

- Don’t interrupt silences when the interviewee is thinking.

- Don’t paraphrase if you do not have to. There is a reason your interviewee said it that way.

Return to Top of Page

American Life Histories. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/wpaintro/wpahome.html

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. “Oral History Interview Guide.” http://www.hsp.org/.

JewishGen. "Oral History Questions." http://www.jewishgen.org/InfoFiles/

Moyer, Judith. “Step-by-Step Guide to Oral History.” http://dohistory.org/on_your_own/toolkit/oralHistory.html#NOTES, 1999.

Return to Top of Page

American Life Histories. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/wpaintro/wpahome.html

Fallaci, Oriana. 1976. Interview with history. New York: Liverwright Publishing Corporation.

Friedlander, Edward Jay and Lee, John. 2000. Feature writing for newspapers and magazines. New York: Longman.

George Mason University. "What is Oral History?" http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/oral/what.html

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. “Oral History Interview Guide.” http://www.hsp.org/.

JewishGen. "Oral History Questions." http://www.jewishgen.org/InfoFiles/

Moyer, Judith. “Step-by-Step Guide to Oral History.” http://dohistory.org/on_your_own/toolkit/oralHistory.html#NOTES, 1999.

No Train No Gain. http://www.notrain-nogain.org/train/res/reparc/interv.asp.

Oral History Association. http://alpha.dickinson.edu/oha/

Oriana Fallaci. http://www.giselle.com/oriana.html

Southern Oral History Program. http://www.sohp.org/howto/guide/howto_111a.html

Terkel, Studs. 1974. Working: people talk about what they do all day and how they feel about what they do. New York: Avon.

Terkel, Studs. "Conversations with America." http://www.studsterkel.org/

University of North Carolina. "Preparing for the interview." http://www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/oral_history.html

University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives Oral History Program. http://archives.library.wisc.edu/oral/oral.htm

Return to Top of Page

|