Learning to Do Historical Research: Sources

Photographic Images

When Are They Worth a Thousand Words?

Po-Yi Hung

Stephen Laubach

Introduction

Earthrise, 1968

Image courtesy of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

Photographic images serve as powerful records of people, events, and places. They evoke ideas or emotions in ways that words alone cannot. The image above, for example, is one of the most popular NASA images. The Last Whole Earth Catalog refers to it as “the famous Apollo 8 picture of Earthrise over the moon that established our planetary facthood and beauty and rareness (dry moon, barren space) and began to bend human consciousness.”

Yet photography as a medium also has limitations. Reevaluating the old saying “the camera never lies” must be part of using photographs for your research in environmental history. In this web page, we will guide you through the process of evaluating photos for their validity and usefulness, and of using them to help form research questions.

Although we will focus our attention on photography as one representative among many visual media forms, we encourage you to consider exploring other images such as paintings and wood engravings. Two such examples are included below from Harper’s Weekly magazine. These will give you a feel for other types of images that can be used in your research, especially for periods that precede the widespread adoption of photography. Your local librarian can help you locate resources that will guide you through the process of finding and analyzing other visual media.

“Whaling off Long Island – Drawn by W.P. Bodfish”

Wood engraving from Harper’s Weekly, January 31, 1885.

Image courtesy of HarpWeek.

![“The South … [and] the … Mississippi”](photoimages/932_photographic_images_fig03_lowres.jpg)

Wood block illustration by Thomas Nast from Harper’s Weekly, May 13th, 1882.

Image courtesy of HarpWeek.

Table of Contents

Before beginning your research, you must be aware of the copyright laws that regulate the use of most images produced after 1923. If protected by copyright, you should contact the owner to receive permission to use an image. The United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division includes guidelines on its Website for using copyrighted images: www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/rights.html. If you have questions that are not addressed on this link, it is best to ask your local librarian about the issue.

Finding Photographic Images

The first place that many student researchers access for photographs is often the Internet. Some examples of centers with online collections are the New York Public Library Digital Gallery and the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections.

To give you a feel for how to use one of these sites, let’s visit the New York Public Library Digital Collection, http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/index.cfm. Clicking on their collection “Photographic Views of New York City, 1870s-1970s,” you get 54,000 images at your fingertips!

Clearly, you would need to identify a specific research question before proceeding. You could narrow your topic to focus on how the construction of the Empire State Building affected surrounding development in Manhattan. Typing in “Empire State Building” into the search window of the collection yields a more manageable 245 images to select from. Note that each picture is carefully annotated with date, location, and other relevant information.

Be aware, however, that universities, historical societies, and other nonprofits typically have no more than 2% of their photographs digitized or even indexed online. Given the treasure trove of historic photos stored at these sites, we strongly recommend that you take the time to find repositories of photographic images in your area to supplement those you are able to find online.

Nonprofits, Universities, and Libraries

The best places to visit are archival centers such as state and local historical societies, universities, and museums or other nonprofits. Some examples of these centers are listed below. Links to their Websites are included in our “To Learn More” section.

United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

California Museum of Photography

Colorado Historical Sociey

Wisconsin Historical Society

Milwaukee County Historical Society

Remember to start by visiting local sites early in your project. If you were researching the rise of Milwaukee’s beer industry, for example, the Milwaukee County Historical Society would be one of the first places to visit for related images. Since their collection is not indexed online, you would need to contact their staff ahead of time about the extent of their archived images on this topic.

When visiting historical societies at the county or city level, be aware that they are often understaffed and may have limited hours. Check their hours early in the research process.

State and municipal agencies may also be a good source of photographic images. If you were interested in how your state’s park system has been promoted with photographs, for example, consider contacting and visiting officials at agencies such as the Department of Tourism and the Department of Conservation (which may go by other names such as the Department of Natural Resources or the Department of Environmental Protection).

Books, old newspapers, magazines, and postcards may contain images useful for your project. Local newspapers and magazines in particular can be a rich source of information on topics that are interpreted differently or overlooked by publications with a national circulation. If you were researching Hurricane Katrina, for example, you could use archived New York Times articles written during the storm’s aftermath, but you would not want to complete your paper without searching the Hurricane Katrina Files of the New Orleans daily newspaper, The Times-Picayune.

Many photographers have published photo-based books that could also assist you. Books by the famous photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984) are perhaps the most widely known for their use of landscape photography, but there are many to choose from in this genre. In his book Second View: the Rephotographic Survey Project, for example, the author Mark Klett pioneers the concept of rephotography. Klett juxtaposes historic photos with still shots that he has taken from the same location several years or decades later.

You may find that the approaches of photo-book authors give you additional ideas for including your own photographs in your research. Although it won’t be possible to achieve the same level of precision as Mark Klett with regards to location and camera settings, you may want to experiment yourself with rephotography for your research project by taking a photo from a similar location to an interesting historic photo you have found.

Side view of the Aldo Leopold Shack, ca. 1935-1936.

Image courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Digital Archives.

November 2007 image from similar vantage point with Leopold pines in background.

Photo by Stephen Laubach.

Librarians and Archivists

In the process of visiting libraries and other centers with photographic holdings, you will meet librarians, archivists, and others who will help you find resources that would be difficult to locate on your own. Don’t be shy about seeking them out. Make sure to learn the names of those who have assisted you and to thank them personally.

Return to Top of Page

Viewing Photographs Critically

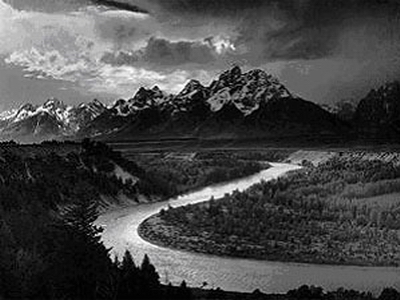

The Tetons and the Snake River by Ansel Adams

Image source: Wikipedia entry: Ansel Adams

Notice the viewing perspective

Different perspectives used by photographers not only relate to artistic purpose, but also to the different relationships between the objects in the photo and the viewers. Take vantage-point perspective as an example. A vantage-point location could be a high place, a hill, or the top of a tower. Such a vantage-point perspective disengages the viewers physically from the objects viewed to create a panorama.

Look at the famous photo, The Tetons and the Snake River, taken in 1942 by the renowned photographer Ansel Adams. The vantage-point perspective produces an aesthetically stunning image of the landscape. At the same time, it distances the viewers from the trees, rivers, and mountains to create a birds-eye view of the landscape. This view could therefore enhance the connection between humans and wild places, or it could lead to a sense of human domination over nature.

Look into what is seen, and think about what is not seen

Remember that the content of a photograph only contains partial stories regarding a place or an event. Within a picture’s frame, photographers cannot include all elements they witness. However, this constraint also means that photographers are privileged to select, frame, and compose what is seen. In other words, in order to critically analyze photos, always think about the resulting significance about what appears and what is missing in the content.

Again, take a look at Ansel Adams’ photo, The Tetons and the Snake River. The photo only contains elements commonly categorized as nature, be they snow peaks, the winding river, or the lush forests. Accordingly, the landscape in the photo may imply that the Tetons are wilderness with pure and uncontaminated nature, away from any human disturbance. As a result, this framed image of pure nature could neglect the relationship between the landscape and existing human cultures around the Tetons. Consider the way it may thus reinforce the imagination of wilderness prevalent in American culture.

Carefully read any text describing the image

Notice that the content of photos often includes attached text describing an image. Such information is important not only because it denotes the photographer’s motivation for taking the photo, but also because it, explicitly or implicitly, often discloses the social values or ideologies embedded in the image. The text could be directly written by the photographer, by the institutions that use the image for their purposes, by critics of different social backgrounds, etc.

The photo The Tetons and the Snake River may exemplify Ansel Adams’ words in his 1983 autobiography: “I know that I am one with beauty and that my comrades are one. Let our souls be mountains. Let our spirits be stars. Let our hearts be worlds.” These words, combined with the image, help you become familiar with the photographer’s philosophy concerning human-environment relations. Here, investigating related texts is essential to help understand how photos have become a powerful influence on the history of environmental protection.

Consider Who Took or Made the Image

Get information about who made the image

Knowing the background of the photographer or the institution producing the photo is a critical step in interpreting the motivation behind making the image. Ansel Adams, again, is a good example. If you only know him as a landscape photographer, you probably appreciate his works from the viewpoint of his artistic achievement. Nevertheless, if you realize that Adams was also an environmentalist who used his photos to express his belief in preserving nature, the way you approach his works could be reoriented to an inquiry into the relations between images and the development of environmental protection in the United States.

Historical context matters! Always think about when the image was produced

You will risk misinterpreting a photo if you don’t pay attention to the context when the image was produced. If you look into Adams’ photos without situating his works in the context of American society, you may interpret his photos only from the perspective of how he was inspired by nature. On the other hand, if you contextualize his early works in his formative years of the 1930s, you can realize critical stories behind the photos.

Many 1930s American photographers took their photos out of a sense of obligation to reveal the harsh times of the Great Depression. Critics call it the “art for life’s sake” movement. Knowing this historical context, you may realize that the motives behind Adams’ “natural” photos produced in the 1930s were different from the motives of this movement. You could therefore try to gain insights into how Adams’ early works shifted focus away from the “art for life’s sake” movement and were instead deployed in the cause of wilderness preservation.

Think about How People Interpret and Use Images

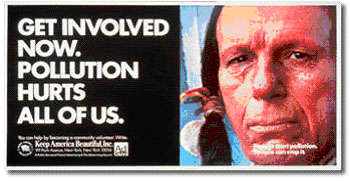

Keep America Beautiful's famous 1971 Ad Campaign, featuring Iron Eyes Cody, the "Crying Indian"

Image source: Wikipedia entry: Keep America Beautiful

Examine how the image is read among different social groups

How viewers interpret a photo is not always consistent with the original purpose or intention of its producer. Moreover, the same photo can be read and interpreted in different ways by different social groups. These differences can be critical for understanding different positions concerning a specific environmental issue. Take the famous 1971 “Crying Indian” image above as an example. Although it was used to promote environmental concerns, social groups approached the image differently.

The environmental organization that produced the image of the Crying Indian used it for a campaign criticizing industrial pollution and promoting environmental protection. Many American Indians used the image to articulate their identity, emphasizing the harmonious relation between Indian cultures and nature. Thus, the example of the Crying Indian could help you understand how different social groups approach an image. It demonstrates how Indian cultures have been appropriated by environmental organizations to reinforce tensions between nature and the modern industrial world. It also suggests how American Indians positioned themselves in these tensions.

Think about how the image is used in different social contexts

Not only is it important to ask how an image is used among different social groups, it is also important to ask how the same image is packaged and interpreted in different social contexts. One thing to notice is that people’s interpretations of a photo are not fixed based on a pre-assigned categorization of different social groups. You should not assume American Indians, for example, are a unanimous entity that always understands an image in the same way. Rather, within any specific social group, like American Indians, the meanings of an image change depending on when, where, and by whom they are viewed.

Again, look at the image of the Crying Indian above. Iron Eyes Cody, the Crying Indian, is actually Sicilian, not American Indian. In 1996, his Sicilian heritage was reported by the New Orleans Times-Picayune. Consider how this may change the meaning of the image and convey the politics of identity implicated in the environmental movement.

Finally, while many American Indians embrace the narrative of “the ecological Indian” associated with the iconic image, some Indians may be concerned more about the condescending stereotype of “the noble savage” implied by the image. In other words, to understand how the meanings of the Crying Indian image change in different scenarios, you could pay attention to when, where, and why the different meanings—be they the ecological Indian or the noble savage—have been purposefully highlighted.

Return to Top of Page

Using Photos to Form a Research Question

Now that you have an idea of where to find images and how to interpret them, what is a strategy for viewing photographs that will help you form a specific research question? In his book Handbook of Visual Analysis, Malcolm Collier outlines an approach to photographic analysis that we will explore below using aerial photos. First we will describe the process, and then in the “Try This…” section that follows we will apply the process to the aerial photos.

In image analysis, the researcher examines the content of photographic images in a search for patterns and meaning. Imagine that you are interested in land use and the relationship between farming, housing, and commercial development. You could examine aerial photos from the same location over several years and assess changes in housing density, location of shopping centers, and the number of farm parcels in two or more photos of the same location. We will try this approach below with three aerial photos.

2002 Aerial photograph of Lawrenceville, New Jersey.

Image courtesy of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

1974 aerial photo of Lawrenceville, New Jersey

Image courtesy of Aerial Viewpoint, Houston, TX, (800) 784-5801

1940 aerial photo of Lawrenceville, New Jersey.

Image courtesy of Aerial Viewpoint, Houston, TX, (800) 784-5801

Stage 1

Observe the images as a whole and search for patterns. Write down first impressions and note all questions that come to mind. Decide which question you are most interested in pursuing for your project. Take into consideration which research questions are most likely going to lead you to the documents you might need.

Stage 2

After gathering two or more images, examine them individually, attempting to gather evidence to answer your question. Quantify when possible – e.g., number of cars, houses, farm parcels, etc. Refine your chosen questions and pose new follow-up ones.

Stage 3

Step back and return to the “big picture.” Reexamine the visual records in their entirety and consider what patterns emerge when comparing different photos to each other.

Images in Oral History Interviews

In this approach, the researcher uses photos in the interview process to elicit more specific and detail-rich information from an interviewee. Photos used in this way serve as natural gateways to stories in a way that simply asking a question may not. This underutilized type of image analysis can be a valuable way to “break the ice” with an interviewee. If you use this form of image analysis, you must label your photos ahead of time and take detailed notes in order to keep track of which photos are associated with which responses. Be aware too that this method is not equally effective for all interviewees—some people may respond better to other cues.

Return to Top of Page

Imagine that you are from the central New Jersey town of Lawrenceville shown in the aerial photos above. This semester you are working on a paper in which you are asked to research the environmental history of your home. You recently moved to the area and never really noticed how out-of-place the farm fields in the central and eastern portions of the 2002 aerial photo look. Maybe these farm fields offer a clue about New Jersey’s mysterious state motto, “The Garden State.”

You consider our earlier guidelines for viewing photographs critically. What are the strengths of these images in terms of photographer background and image documentation? Why were the photos taken? What are the drawbacks to using birds-eye perspective aerial photos for environmental history research?

Image Analysis

Stage 1

Viewed together, several questions and sub-questions could be asked which would require you to extend your research beyond the images themselves. Some examples include:

Why did the ratio of farm fields to housing units remain relatively unchanged between 1940 and 1974?

What kinds of crops were grown on these farms?

How did the farmers bring their crops to market?

Why was there a dramatic decline in farming between 1974 and 2000?

How can the remaining farm fields in the 2002 aerial photo continue to operate?

Who owns that land and who farms it?

What crops are grown there and what kind of revenue do they provide?

Now take a moment to develop your own additional questions. Topics could include road networks or location of forests, streams, and ponds.

Stage 2

Suppose the question you chose to answer leads you to scrutinize the 1940 and 1974 photos. You recognize a road familiar to you that stretches from the southwest to the northeast portion of the photos as US Route 206 – the historic “King’s Highway.” Connecting Trenton to the south with Princeton to the north, George Washington’s troops marched along it on their way to the Battle of Princeton in 1777.

In 1940 and 1974, Lawrenceville is a rural outpost between these two cities.

In 1940, there is a stream in the eastern third of the frame that runs north-south and is surrounded by farmland.

In 1974, this stream is surrounded by woods.

In 1974, all development occurs to the north of Rt. 206

Take a moment to make some additional observations from the 1940 and 1975 photos.

Stage 3

Step back and return to the ‘big picture.” Reexamine the visual records in their entirety and consider what patterns emerge when comparing different photos to each other.

Overall, parts of several farm fields have reverted to forest. You wonder why this change has taken place. Was the land marginal for farming? Were there laws passed that required buffers between streams and farming activity?

Farming continues to be economically viable in this area through at least 1974. A visit to the website of the local farmers market in Trenton gives you some idea of how farmers bring their goods to market.

You also discover from the Lawrenceville Public Library that the township has a local Lawrence Township Historical Society, and that the society will be able to help you learn more about Lawrenceville’s farm history.

Images in Oral History Interviews

Continuing on the topic above about farming in New Jersey, you come across the photos below on the website of the Trenton Farmer’s Market. You contact the market’s managers and set up an interview to ask them about the history of farming in the Lawrenceville area. To help stimulate the discussion, you bring some copies of print (non-digital) photographs you’ve encountered with the help of the Lawrence Historical Society, and you print up the photographs below that are on the market’s web page.

The photos can help guide the questions you ask. They clearly suggest that the transportation modes of farmers and their customers changed radically from the 1900s to the 1950s, from horse and buggy to automobile. The shift in the location of the farmers market could also influence your discussion. The 1900s photo has at least four smokestacks visible in the background, a feature not seen in the 1950s photo.

Take a moment to think about how you can meaningfully synthesize the patterns you have observed during the process of image analysis. You could ask the market’s managers questions that connect the photos below with what you have learned about farmland in Lawrence from the aerial photographs. Consider questions about the photographers as well, such as who took the photos and what their purpose in taking them was.

The Trenton Farmer’s Market in the early 1900s.

Image courtesy of the Trenton Farmer’s Market.

Trenton Farmer’s Market at its new location in the 1950s.

The market is now in the same location as the 1950s photo.

Image courtesy of the Trenton Farmer’s Market.

Return to Top of Page

- Do Visit your local historic society and libraries and get to know their staff.

- Do compare photos with other forms of data such as oral histories or written documents.

- Do assess the perspective of the photographer.

- Do think beyond what you see in an image.

- Don’t violate copyright laws when using photos.

- Don’t always think of photos as an “objective” view.

- Don’t rely on the internet as your sole source of historic photos.

Return to Top of Page

Adams, Ansel. 1997. America’s Wilderness: the Photographs of Ansel Adams with the Writings of John Muir. Edited by Elaine M Bucher. Philadelphia: Courage Books.

Colorado Historical Society. “Library.” http://www.coloradohistory.org/chs_library/library.htm

George Eastman House. http://www.eastmanhouse.org/

New York Public Library Digital Gallery. http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/index.cfm

The Center for American Places. http://www2.colum.edu/american_places/

United States Library of Congress. “Prints and Photographs Reading Room (Prints and Photographs Division).” http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/catalog.html

United States Library of Congress. “Rights and Restrictions Information.” http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/rights.html

University of California Riverside California Museum of Photography. http://www.cmp.ucr.edu/

University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. http://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/index.shtml

Wisconsin Historical Society. “Wisconsin Historical Images.” http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/whi/

Return to Top of Page

Links and Works Consulted

Adams, Ansel. 1983. Ansel Adams: An Autobiography. Boston: Little Brown and Co.

Aerial Viewpoint. www.aerialviewpoint.com.

Collier, Malcolm. Approaches to Analysis in Visual Anthropology. In Handbook of Visual Analysis, ed. Theo van Leeuwen and Carey Jewitt, 35-60. London: Sage Publications.

HarpWeek. http://harpweek.com/.

Klett, Mark. 1984. Second view: the Rephotographic Survey Project. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Klettt, Mark. 2005. Third views, second sights: a rephotographic survey of the American West. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press in association with the Center for American Places.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “NASA Images.” http://www.nasaimages.org/

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. “Geographic Information Systems.” http://www.state.nj.us/dep/gis/index.html

Portola Institute. 1971. The Last Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools. Menlo Park: Portola Institute. Distributed by Random House.

Trenton Farmer’s Market. “History.” http://www.thetrentonfarmersmarket.com/.

University of Wisconsin Digital Archives. “Images from the Aldo Leopold Papers, 1903-1948.” http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/EcoNatRes.Aldo

Return to Top of Page

|