Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer

Drafting, Revising, and Editing

How to Get the Dead Dogs and Leaning Chocolate Cakes out of Your Paper

Genya Erling

Trish O’Kane

Introduction

You can think of writing like baking a chocolate cake except that you are going to bake three or four chocolate cakes. The first two or three will look like the Leaning Tower of Pisa or have a big canyon in the middle or might be oozing a strange substance, so you’ll feed those to your roommates or your dog (well, don’t do that because chocolate can kill dogs).

Wait, what? Dead dogs? No, that doesn’t sound right! Let me try again.

You are about to give birth to the best environmental history paper ever written. You will immediately feel attached to it. You will think it is the most beautiful creature in the world even though it is all red and wrinkly and makes strange noises. But you’re going to have to chop off its toes, maybe even its head, and you might have to throw it out the window altogether. So don’t get too attached.

Eww! Now that’s just grotesque! How about:

You’ve made it this far. You have all of your lofty ideas, solid evidence to support your arguments, and even illustrations, but you sit down at your desk and find you can’t get past your name and date. The sentences feel awkward as you type them. The words don’t seem to flow. It starts to feel like all the work you’ve been through so far is for nothing! What can you do?

Well, it’s kind of boring, but at least it’s not morbid. I’ll stick with it for now.

Sound familiar? For many people, writing can be the most frustrating and traumatizing phase of the research process. But it doesn’t have to be this way! We are here to share some tricks to make it through the drafting phase smoothly.

Table of Contents

Prewriting: Setting the Mood

“Sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’”

—Ernest Hemingway in A Moveable Feast

Because so many people find writing difficult, they tend to avoid it as long as possible, finishing just before the deadline and not taking the care required for quality revisions. The writing ends up dry and wordy, replete with spelling errors and comma splices, barely held together with an argument that wanders. These errors distract the reader and discredit the writer.

Don’t let it happen to you!

You can avoid falling into this trap by starting early, getting organized, and getting busy with writing, revising, and editing. If you start early enough, you will have time to go through the process several times before you have to turn it in, and you will have a perfectly polished final draft.

If You Didn’t Start Early

Let’s be honest, though. People always procrastinate, and more than likely, your paper is due in less than a week. But even if your paper is due in a few hours, making the effort to draft and revise your work with care and consideration will make all the difference! In fact, sometimes that last minute pressure is just what you need to break your writer's block. Take advantage of that adrenaline rush, but don’t be too hasty! A game plan is critical!

One of the keys to successful writing is finding a comfortable space to think. Find out what works best for you.

Where?

Few places are more comfortable than your own home, but if you know you’ll be distracted by friends and family, or driven to snacking, cleaning, and other forms of procrastination, get out of the house! Try the frenetic energy of the local café for inspiration. Or for a quieter space, go back to the library and find a corner. Feel the wisdom of the dusty stacks of books leading you to successful writing!

Find a Place to Write That Works for You

(Photo by Genya Erling)

When?

If it’s the night before a paper is due, you don’t really have much choice with this one. If you have a little more time though, allow yourself to focus your energies at the times when you will be the most efficient. At what time of day do you feel the most focused? Try getting up early in the morning to write. The crisp stillness of the dawn can be calming and conducive to writing. Brew a fresh cup of coffee and listen to the first chirp of the birds as you sit down to write your paper. Or perhaps you would feel more comfortable later in the day, after you’ve had time for other responsibilities. Some work best under the pressure of nightfall.

Return to Top of Page

Put All Your Cards on the Table: Outlining

Maybe you’re very diligent and it’s two weeks before your deadline. Maybe it’s 10:00pm and that paper is due at 8:00am tomorrow morning, so you face a night romancing the coffee pot and pounding on your computer keyboard. Whatever the case, this exercise below can help you organize your thoughts before you write. If you know what you want to say before you start writing, the process will go much faster and be a lot easier.

You've done piles of great research, and finished the hunting and gathering stage. By this time you’ve become an expert of sorts on your chosen topic. The more research you’ve done, the easier it will be to write. It’s time to get out your road map and figure out where your paper is headed.

- You need a big space to see the big picture, so clear the kitchen table.

- Get out your outline, all note cards, and/or print out your computer files.

- Keep the outline in front of you.

- Pile all the cards or files in categories so you can see what you've got.

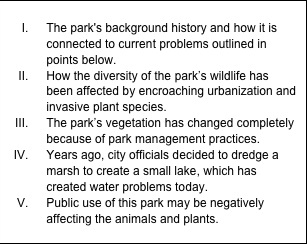

Put All Your Cards on the Table

(Photo by Trish O'Kane)

Hopefully, the categories match the main points on your outline. You may have picked up a new category or two during the research process.

Read through the piles and find the juiciest tidbits.

Take out the cards with boring or useless information on them and set them in a “junk” pile. You're going to organize your paper around your best stuff.

Now take your original outline and compare your piles to your main outlined points.

Example:

So you are writing a paper on the environmental history of a local park. Your original outline has these main points:

Your note card pile on park history is the tallest, full of information on who designed the park, how the land had to be altered to build it, etc.

Your pile on park wildlife is a bit anemic, although you did find a cute story online about how children at a local elementary school wrote short stories about the park's deer population. But you weren't able to interview the city’s wildlife biologist and so you don't know exactly how and why the diversity of the wildlife population has changed over time. The public library had good books on the area's vegetation history so you're covered there.

Your best pile is on water issues. The local newspaper published several articles on the area's lakes and rivers and there was a story about a fish kill in your park's lake. You followed up on those stories by examining an aerial photo archive of how the city dredged the lake, studying historic land survey maps of the area, by interviewing the city's ecologist, and by listening to oral histories in the university's oral history archive; there was a treasure trove of interviews with elderly fishing club members.

The information in your final pile on people's uses of the park dovetails with the water issues pile because the lake is a popular fishing and boating spot.

Overall, your best stuff is in the history pile, the water issues pile, and the public uses pile. We know that you're passionate about the secret life of squirrels and wildlife biology but you don't have enough information. Those Bambi spinoff stories by schoolchildren about the park’s deer population were cute but they just don't fit.

The vegetation history is interesting but you need to find a way to link it to the other points--just talking about the fabulous bicentennial Burr Oak in the middle of the park might fill a page or so, but so what? So take the vegetation and animal piles off the table and file them away. You can use a few juicy details from them when you paint a word picture of the park in your brilliant introduction but they are not part of your main story.

Write a leaner, meaner new outline based on the piles that are left.

Hopefully you see a clearer storyline after doing this exercise: the park is an ecological mess because of regional water mismanagement and housing development, and that is because of several complex factors. Now skim through the piles one more time and compare them to the points on your new outline. Do you have enough information right now to tell a good story and support these arguments?

If so, you are ready to write, so skip to the next section.

If not, make a list of what information you are missing.

- Remember that you have little time left to finish this paper so you can't do much more hunting and gathering.

- If you are still having trouble figuring out the main story line, you need a quick consultation with your university's writing center. Get online right now and make an appointment, and be sure to take your outline and all notes.

- If you know the story line and you are missing just a few key pieces of information, go see that friendly librarian who helped so much on the first day. Take your new outline, tell them what is missing, and maybe they can lead you to a new government report on local water issues or a book on park management. Fill in those information holes and then you will be ready to write.

If this outlining exercise above did not help you and you are still stuck, take a look at your piles and ask yourself, what is the main story? If you don't know, what did you find most interesting while you were doing the research? What makes you angry, sad, excited about your discoveries? When your roommates ask what you have been working so hard on, what is the one-minute blurb that you tell them about this fascinating park? You need to make sure you have answered the what and the why: what is this park like and why is it this way?

Before you go any further, complete this sentence:

In this paper I argue that ________, and this is important because ________.

If you are still confused about what the story is, call your mother, your girlfriend—someone who will listen. Talking through your paper is also a good way to organize your thoughts and prime your creative pump for writing.

Finally, the best and fastest way to get help, before you write and throughout the writing process, is to get into your university’s writing center, immediately. There are full-time writing tutors there who will work with you individually, for as long as you need, until that paper is fixed. This service is free and if you use it for all your papers, you can dramatically improve your writing skills and your grades. Even if you think you’re Ernest Hemingway, you should develop a relationship with a writing tutor at the writing center and use this service throughout your college education. There is nothing like a discerning, kind, and patient editor.

Return to Top of Page

Drafting: Just Do It

For me and most of the other writers I know, writing is not rapturous. In fact, the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.... Start by getting something—anything—down on paper.... The first draft is the down draft—you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft—you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even God help us, healthy.

—Author Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

Now it’s time to write what Anne Lamott calls "that shitty first draft." This phase of the process is crucial because it is here that the secrets of your story will reveal themselves. Even with the best made outlines and notes, you will not have a real sense of your ideas until you start trying to put them on paper.

Here’s how you do it:

Just sit down, either with a pen and paper or at your computer, and start working.

Different things work for different people. Try to type your table of contents first. It will give you a structure within which to work.

If that doesn’t work, then try dumping all the stuff from your brain onto the page or screen. Start with the introduction and just free-write and see how it goes. Then you can put all those horrible metaphors and dangling participles into your computer.

Another option is to type out all of the quotes you’d like to use. That way, at least you have words on the page or screen, and that sense of accomplishment can be just the thing to get you into the writing groove.

If you are still petrified, move to the section you like best, the one that will be easiest for you to write. Grab that gorgeous little pile of note cards and start entering all the most important information in your computer.

Pound away as you listen to your favorite music, but only if it doesn’t distract you.

Power your way through it and then print out whatever you have.

Return to Top of Page

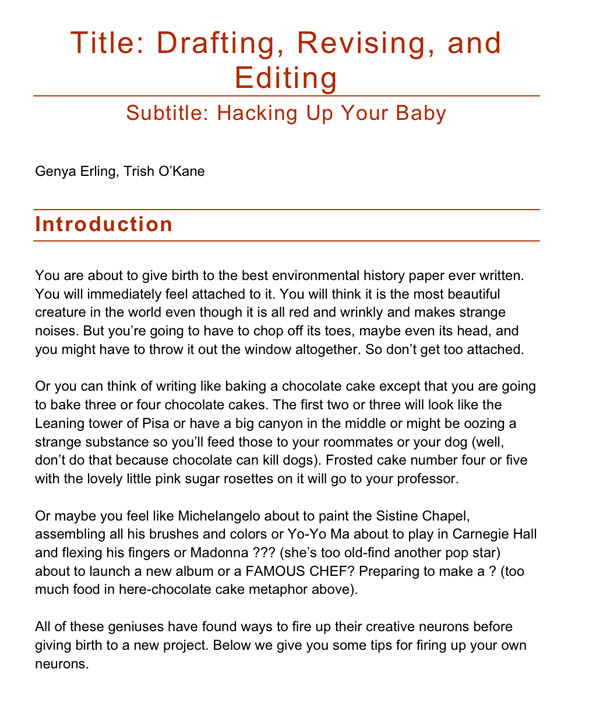

Normally, you will never show your first draft to anyone – after you analyze it, you want to hide it away in your files for a laugh another day. For the sake of providing an example, though, let’s look at that terrible introduction again.

Our Shitty First Draft for this Webpage

(Photo by Genya Erling)

Now you know why you never turn in a first draft of a paper!

But don’t throw it away just yet. Here’s how you can analyze and learn from a truly awful first draft:

- Our first draft above has a serious audience problem. We are writing for college students and the hacking up the baby metaphor seems a bit gruesome. We’re supposed to make writing fun and seductive. So lesson one is: remember your audience. You’re writing for your professor so read and reread the assignment sheet and follow it. Also remember that in this age of instant web-publishing, you might be writing for a general public if your teacher decides to post your paper, so make it appropriate to a general audience.

- Our first draft also has a serious simile problem. We love chocolate cake but when you are drafting a paper you don’t throw the whole thing out or feed it to your dog--you keep the good parts, add more stuff, and keep working on it. And what are chocolate cakes that lean like the Tower of Pisa and dead dogs doing on this webpage anyway? But that’s what shitty first drafts are for—to get the frosting out of your head.

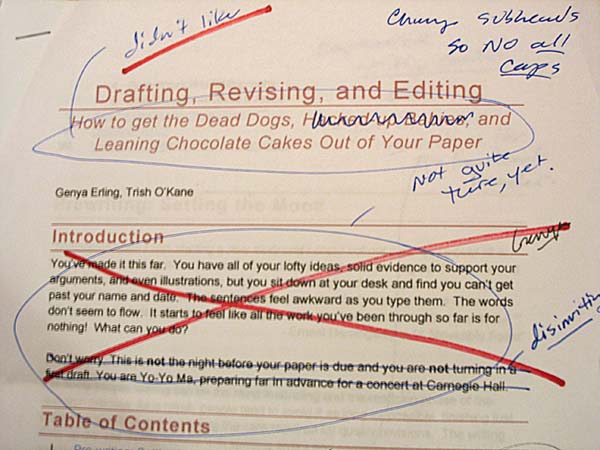

Marked-Up Draft

(Photo by Trish O'Kane)

Keep all of your drafts. Your best ideas may be buried at the very end of six pages of junk. Cut and paste those ideas into a “Draft 2” file and get going on your second draft. Remember that every good paper needs a strong beginning and a strong end. If you can write an engaging, descriptive introduction that clearly explains what the paper is about, you will gain confidence. You have a good outline. Stick to it and try to write through each section, putting in the data you have on your note cards or in your computer files.

Return to Top of Page

Finished! (Well, for Now)

After five cups of coffee and two sleepless nights, it's finally done. Proudly you print out your paper and feel its weight in your hands. Now put it away for 24 hours in a drawer and forget about it. No sneak reading of it. No talking about it. Leave it in the dark and get a good night's sleep.

Return to Top of Page

Revising: Writing is Rewriting

We tell stories with each other and against each other in order to speak to each other. Our readers, in short, play crucial roles in shaping the stories we tell. Just so has this essay gone through four separate incarnations to reach its present form, each of them responding in different ways to the critical communities that in a very real sense helped author them. No matter how frustrating this process of revision may be, the resulting text is in this case unquestionably better as a result.

--- William Cronon in "A Place for Stories: Nature, History, and Narrative"

Tools for a Self-Critique

Once you’ve given the paper some time to breathe, go back to it. Read through it carefully, preferably aloud, and ask yourself the following questions:

Structure:

- Is the central argument clear and easy to identify?

- Is the paper well organized with logical progressions?

- Are the main points easy to follow?

- Have you summarized each section at points of transition?

- Does each paragraph form a discrete and coherent argument?

- Does the paper start strong and end gracefully, rather than just dribbling off?

- Is there a better way to organize this paper?

Style:

- Are quotes well integrated into the argument? Have you identified the speaker?

- Are you using signposts and transitions to communicate effectively?

- Does the writing flow smoothly with clear transitions?

- Is the language clear?

- Is the language vivid?

- Are there errors in spelling, grammar, or punctuation?

- Are there run-on sentences or sentence fragments?

Content:

- Does the introduction grab the audience’s attention?

- Are the claims valid and substantiated?

- Are you being too vague with your claims?

- Is the writing alive with detail (the pink rosettes on the chocolate cake, the potato soup with three potatoes in it)?

- Is every opinion or argument backed up by facts?

- Have you made sure that your reader can always tell when and where a given event is taking place?

- Is the topic handled creatively?

Give your paper to a roommate or friend to read. Tell them you want to meet with them the next day to get their reaction. Give yourself 24 hours away from this paper.

When you meet your reader the next day, they will probably tell you that your paper is wonderful. Do not believe them. No first draft or second draft is wonderful. Michelangelo did not paint the Sistine Chapel after one sleepless night.

Thank them for their efforts and ask them not to look at the paper for a minute. Ask them: what was the main point of the paper? If they didn't get it, you have a problem. Your introduction and conclusion probably are not clear enough. You need to begin strong and end strong so highlight your introduction and conclusion.

Also ask your reader to show you all the places in the paper where they did not understand something you wrote. Highlight these passages—they are problems. Ask your reader what questions they had after they finished reading the paper.

If you do not have potential readers, make an appointment with those great tutors at the writing center. Have them go through the first and/or second drafts with you. We know we’ve told you this before, but we’re going to say it again. The single best thing that you can do for your university writing career is to develop a relationship with a writing tutor at your university’s writing center. They are paid to help you--take advantage of it. After college you will need good writing skills for almost any job. This is not about a grade—this is about your life.

It is not unusual for a professor to assign a presentation in addition to a written report. Others might assign a peer review or a rough draft. It might seem like they are just trying to torture you, but don’t waste this valuable opportunity for feedback! You will gain important insights from hearing other perspectives. In fact, the process of creating this chapter has involved collaboration with the whole class, and it would not be in its current state if it weren’t for the suggestions and critiques of its many members.

Rewriting: Do It All Over Again

Think you’ve made it to the end? We hate to tell you, but this is just the first round. Now you get to do it all over again. Don’t worry. It will be easier this time. You have gotten good feedback and are feeling comfortable with the organization. Now take what you’ve learned and iron out the wrinkles.

Rewrite Draft 1 or 2 based on your reader's comments and your own reading. Fix any rough spots that are left. Crank out draft three or four.

If you have time, give it back to your reader or another reader. Ask them the same basic questions:

What is this paper about?

What did they learn?

What didn't they understand?

Write it again.

Return to Top of Page

Editing: Polishing Your Diamond

“I’ve never published a word that I hadn’t heard going over my tongue because [of] the relationship of one sentence to another sentence. A perfectly good sentence may have to be changed because sentence number two makes it a little awkward rhythmically.... Number three does that to two and one and so on. That’s why first drafts are so awful. A significant goal for me is just to hear this thing and I read it generally to my wife…then I go back to work on it, make the rhythm better.”

—John McPhee, National Public Radio, June 24, 2006

One More Time: Make the Rhythm Better

Finally, for the final polish, do what John McPhee does with everything he writes and read that draft aloud. If you can assemble your roommates for an impromptu reading, do it. Bribe them with a pizza and beer. Have a pen ready. Wherever you stumble, there's something wrong. Highlight all those places. Are there sentences you have to read two or three times to make sense of them? Highlight and fix them.

(source unknown)

-

Verbs HAS to agree with their subjects.

-

Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.

-

And don't start a sentence with a conjunction.

-

It is wrong to ever split an infinitive.

-

Avoid cliches like the plague. (They're old hat.)

-

Also, always avoid annoying alliteration.

-

Be more or less specific.

-

Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are (usually) unnecessary.

-

Also too, never, ever use repetitive redundancies.

-

No sentence fragments.

-

Contractions aren't necessary and shouldn't be used.

-

Foreign words and phrases are not apropos.

-

Do not be redundant; do not use more words than necessary; it's highly superfluous.

-

One should NEVER generalize.

-

Comparisons are as bad as cliches.

-

Don't use no double negatives.

-

Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

-

One-word sentences? Eliminate.

-

Analogies in writing are like feathers on a snake.

-

The passive voice is to be ignored.

-

Eliminate commas, that are, not necessary. Parenthetical words however should be enclosed in commas.

-

Never use a big word when substituting a diminutive one would suffice.

-

Kill all exclamation points!!!

-

Use words correctly, irregardless of how others use them.

-

Understatement is always the absolute best way to put forth earth-shaking ideas.

-

Use the apostrophe in it's proper place and omit it when its not needed.

-

Eliminate quotations. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "I hate quotations. Tell me what you know."

-

If you've heard it once, you've heard it a thousand times: Resist hyperbole; not one writer in a million can use it correctly.

-

Puns are for children, not groan readers.

-

Go around the barn at high noon to avoid colloquialisms.

-

Even IF a mixed metaphor sings, it should be derailed.

-

Who needs rhetorical questions?

-

Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

-

Avoid "buzz-words"; such integrated transitional scenarios complicate simplistic matters.

-

And finally... proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

And finally...

- 35. Proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

Return to Top of Page

Print out a clean copy of your paper and highlight every name, number, quote, and reference. Check your notes to make sure that you got all those quotes right. One misspelled name can discredit the whole paper. You’ve worked too hard to be sloppy at the last minute, so make sure that you check every fact carefully. Also check your notes to make sure that you did not inadvertently plagiarize.

Style Sheets for Your Citations and Bibliography

Your professor has assigned a stylebook for your class. Hopefully, that helpful book is sitting on your desk right now, next to your dictionary. If not, you can probably access it online, as well. It is probably the The Modern Language Association (MLA) Handbook or The Chicago Manual of Style – two books that will serve you well throughout your college education. Follow the stylebook’s instructions for footnotes and bibliography. Remember to work carefully and pay attention to details. Punctuation matters. You’ve worked so hard on your paper – you don’t want to lose points because of misplaced commas or periods. Also, make sure to reread the professor’s assignment sheet and follow instructions on how to present and turn in your paper.

Return to Top of Page

Tips for Beating Writer’s Block

After hours of sitting scrunched up at the computer, you probably are not breathing very well, which means that you are not thinking very well. Get up and get some oxygen flowing into your brain. Close down the computer, put away all your paper files, and go exercise vigorously. Take a walk. Go to a yoga class. Go running. Play with your dog.

Let Me Help You with Your Writer's Block

(Photo of Little Bear by Trish O'Kane)

You can also fire up your creative neurons by engaging in another creative activity. If you play a musical instrument, it’s time to serenade the neighborhood on your saxophone or clarinet. Sing at the top of your lungs. Draw. Knit. Bake a chocolate cake or make oatmeal chocolate chip cookies for your roommates. Do the laundry. If you’re a gardener, get outside and plunge your hands into the moist earth. As you weed the arugula, your brain will be weeding out all those extraneous sentences that have crept into your paper. Whatever you are doing, keep your hands moving as you create something; you may suddenly have a breakthrough on how to write that strong, seductive introduction or that masterful conclusion.

Return to Top of Page

Do:

- Do use active language rather than passive—"The French chef baked the chocolate cake" instead of "The chocolate cake was baked by the French chef"--and try to use interesting verbs like “sprinted” instead of “ran.”

- Do show rather than tell. Use details. Paint a word picture of the place you are writing about. Use the specific names of plant and animal species to enrich the texture of your writing. Instead of “the meadow was ringed by low shrubs,” write “the meadow was ringed by staghorn sumac and buckthorn.”

- Do write clearly. Earnest Hemingway believed that less is more when it comes to good writing. Try to make every sentence an absolutely true sentence.

Don’t:

- Don’t fill your paper up with big words to try to impress your professor.

- Don’t use clichés – they are boring.

- Don’t use jargon. Explain any term that a general reader may not understand or do not use it.

Return to Top of Page

Bernstein, Theodore M., The Careful Writer: A Modern Guide to English Usage, New York: The Free Press, 1965.

Cronon, William, "A Place for Stories: Nature, History, and Narrative," Journal of American History, 78:4, March 1992, p.1347-1376.

Cronon, William, “Suggestions for Writers,” www.williamcronon.net/handouts/Writing_Rules.pdf

Goldberg, Natalie, Writing Down the Bones, Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1986.

Lamott, Anne, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, New York: Random House Publications, 1984.

Lanham, Richard A., Style: An Anti-Textbook, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

Ross-Larson, Bruce, Edit Yourself: A Manual for Everyone who Works with Words, New York: W.W. Norton and Co. Inc., 1995.

Strunk, William Jr., and E.B. White. The Elements of Style, New York: The Penguin Press, 2005.

Trimble, John R., Writing with Style: Conversations on the Art of Writing, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Publications, 2000 (second edition).

“Rules for Writerers” (Source Unknown) www.williamcronon.net/handouts/Rules_for_Writerers.htm

Return to Top of Page

|