Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer

How to Frame a Researchable Question

Putting Boundaries on Your Research

Po-Yi Hung

Abigail Popp

Introduction

You are interested in doing some research in environmental history, but how do you begin? It can be difficult to select a research topic. You may feel unsure of where to begin, or you may be frustrated by the process. Even though you have a specific topic ready, you could still feel lost when searching for data to support your argument. These feelings are quite normal at the beginning phase of doing research. Developing good research questions is an essential first step of every research project, because good research questions focus your work and provide direction for your next steps. The purpose of this page is to help you learn how to create research questions from general topics, and to give you useful tips for refining your questions during the research process.

Table of Contents

The Importance of a Good Research Question

A good research question defines the focus of your research project. Your research question helps readers to know the specific subject matter you will be addressing within the broad topic of environmental history. For instance, suppose you are interested in market development and its environmental effects. If you asked, "What is the relationship between market development and environmental degradation?” your question would be too broad. This question does not clearly define the problems you are interested in, nor does it put boundaries on your research project. Instead, you could ask, “How did large-scale agriculture contribute to the Dust Bowl in the 1930s?” This is a more specific question. A well-articulated research question provides you and your readers with critical information about your project by defining the focus of your research, its scope, and your motivation.

Dust Bowl farmer driving tractor with young son near Cland, New Mexico

Library of Congress, Digital IDfsa 8b32410

A research question can set boundaries to help you figure out where to go next. A research question defines which data you need to collect and which methods you will use to access and analyze your documents. Again, take the Dust Bowl question in the previous paragraph as an example. By narrowing your question to the relationship between large-scale agriculture and the Dust Bowl, you also narrow the scope of data collection and analysis. You may start archival research focusing on agriculture and settlement history, or decide to conduct oral histories concerning farmers' memories of the Dust Bowl.

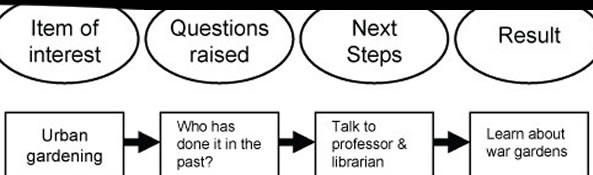

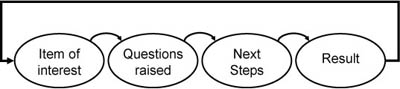

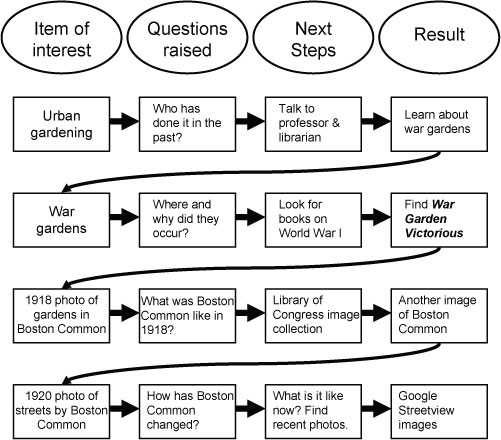

However, as you collect data, your question is likely to change and grow. Defining questions within your project is not a linear process. Rather, questions will define your directions of inquiry and, in turn, the results of your inquiries will refine your question. Developing research questions is an iterative process evolving with your project. We have made a figure below to illustrate the process. You will start with something you are interested in. You will then create questions about this thing, and figure out what your next steps will be to investigate those questions further. As a result, you will (hopefully) learn something new, which will lead to a whole new “item of interest.”

Before you can begin this process, however, you need to find a general research topic.

Return to Top of Page

Consider research you’ve already done. Picking a topic from projects you have done before could help you find ideas that you are already interested in. Collect your previous term papers or reports and list the topics you have researched for those projects. Choose one or two that seem promising and relevant to environmental history. However, you shouldn’t just recycle topics from previously written papers. Instead, you should develop a new topic from the old research.

Your own interests are a great source to find a topic. List your interests (as many as you can!), and then rank them to come up with one or two which are the most compelling to you. One of the best ways to generate a topic from a general interest is to look up encyclopedia articles. They usually contain an overview outlining facts on a subject with a concise list of suggested readings. If you go to the library to find encyclopedia articles, you will have a good chance of finding a topic from them.

Current events or timely issues can be a good place to find a promising research question. For example, Hurricane Katrina brought ideas about poverty and environment into the mainstream press, as well as ideas about land-use patterns and natural disasters. Any of these topics would make a good starting place for an environmental history project. You may read newspapers and magazines, use Wikipedia, or even use Google to find current events. Listen to how people debate these events. What are people saying? What are their claims, and how do they make these claims? Jot down different ideas and perspectives, ask yourself whether you agree or disagree, and try to formulate interesting questions about what you are reading.

People sit on a roof waiting to be rescued after Hurricane Katrina

Photo courtesy of FEMA, 2005. Digital ID 14512

Make a note of your everyday observations. You may find a good research topic just from your everyday life. For example, a McDonald’s drive-through facility represents America’s unique fast food restaurant landscape. Think about why this particular type of landscape (highway systems and road systems) formed. Doing so will help you to come up with a research topic investigating the relationships between highway development and American fast food culture. Remember not to take things for granted. Try to observe through fresh eyes to produce rich research insights.

McDonald's in Times Square, New York City

Released to the public domain via Wikimedia Commons, 2007

Your personal experiences about an event, a social group, or a place are often worth more exploration. For example, suppose that you are a bird watcher and volunteer at a bird conservation society. Recently, you have noticed that it has become harder and harder to spot a specific species in the wild. For this reason, you have decided to participate in an initiative to protect the bird. Your own experiences may help you to look into the relationship between land use change and habitat loss, or make you curious about the historical relation between bird watching and the American conservation movement.

Eastern Bluebird

Released to the public domain via Wikimedia Commons, 2007

Return to Top of Page

Making Your Question Specific

Research is complex and almost always leads to more questions. In fact, research could be a lifelong process of asking new questions and searching for answers! However, for your paper or project you will need to narrow your question down to something manageable within your time frame.

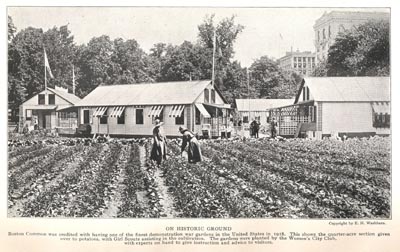

Here is an example of how to generate specific questions from a more general research topic. Let’s suppose you have selected urban gardening as your research topic. How do you move from “urban gardening” to a specific question? One way to begin is to talk to professors. A professor might mention “war gardens” to you, gardens that sprung up during World Wars I and II in all sorts of areas, including urban areas.

While browsing the shelves for material related to gardening during World War I, you find a book on war gardens in World War I called War Garden Victorious by Charles Lathrop Pack. Inside the book, you find this picture of Boston Common, taken in 1918:

ON HISTORIC GROUND

Boston Common was credited with having one of the finest demonstrations of war gardens in the United States in 1918. This shows the quarter-acre section given over to potatoes, with Girl Scouts assisting in the cultivation.

The gardens were planted by the Women’s City Club, with experts on hand to give instruction and advice to visitors.

Photo from War Garden Victorious by Charles Lathrop Pack, 1919.

You’re intrigued by the notion of Boston Common as a garden. You’ve been to Boston Common recently, but there were no vegetable gardens in sight. When and why was it turned into a garden? How long did the garden last? To help you figure out the answers to these questions, you look up some old photos of Boston Common in the Library of Congress. You find this photo of Tremont Street next to the Common, taken between 1910 and 1920. You note that the buildings in this photo exactly match the buildings in the top right corner of the previous photo!

Photo of Tremont Street next to Boston Common, 1910-1920

Library of Congress Digital ID det 4a24958

You realize that these pictures were taken at approximately the same time, from only several hundred yards apart. Yet the photographs give two very different glimpses of Boston Common: one as city garden tended by civic-minded Girls Scouts, the other as bustling metropolitan street with cars, pedestrians, and a subway stop.

With a little more digging, you find a picture of this same street (Tremont Street) in 2008, taken by Google Maps:

Image courtesy of Google Streetview. © 2008

What a difference! The street has been widened, there are far more cars than pedestrians, a new skyscraper has sprung up in the background, and the old subway station appears to be gone. These photos illustrate a few obvious ways in which Boston Common changed over time. But what about the changes that we can’t see in these photographs? Aha! You are getting closer to a research question.

Now take some time to think about what questions these photographs raise for you. How has the landscape of Boston Common changed throughout the years? Why did these changes happen? What can these three photos tell us about people’s relationship to their environment?

Finding a specific research question can be as simple as following a trail of documents until you get closer and closer. Raising questions at every step will help you figure out where to go next. It can be helpful to document your steps while you are looking for a research question so that you can see a path to follow. For the Boston Common example above, your path might look like this:

The Iterative Flow of Questions, Documents, and Research Process

The lesson to take from this is that research is an iterative process. You will go through many of the same steps again and again. You will have to read documents, pursue interesting ideas, read some more, create more questions, find documents, and so on. Continue doing this until you reach a question that is small enough that you think you could answer it in the time available to you. For example, “How has Boston Common changed?” is not specific enough to answer in one semester. However, a question like, “How did the uses of the grounds in Boston Common change during World War I?” might be more manageable for a semester.

If you are having difficulty revising and narrowing your research question, we strongly recommend reading The Craft of Research by Wayne Booth et al. Chapters 3 and 4 in particular focus on defining a researchable question and will give you good advice about thinking through your topic. When you think that you have an appropriate research question, see if you can fill in the blanks in the following sentence. If you are unsure how to fill it in, there are many examples in Booth’s book, or you can consult a professor or peer for help.

I am studying ____________________

because I want to know ____________________

in order to help my readers understand ____________________.

Return to Top of Page

How to Explore Your Questions

This section will suggest some steps you might take while researching your questions. These may fall into the “next steps” category from the diagram above. They can be used at many places in the research process, and you will often do these steps more than once.

Constantly ask yourself: Why then? Why there? Historical research is constantly asking why certain events happened when and where they did. You should always be asking yourself, “What is the historical context that led to this event or situation? Why did it happen at this time and place?”

Search for primary documents. Historical research consists primarily of constructing arguments based on primary documents. You will want to spend significant time exploring which documents are available that are related to your topic. These documents may include photographs, newspaper or magazine articles, recordings, public records, and so on. As always, consult a librarian if you are unsure where to start.

Read scholarly literature. Reading academic literature is critical for you to identify the questions that have not yet been sufficiently studied, to locate your topic within a particular context, and to ask further questions. If you are uncertain how to find the books and articles you may need, you should ask a librarian for help. If you wish to read about how to use a library, we recommend Thomas Mann’s The Oxford Guide to Library Research.

As you read, look for debates and uncertainties. Don't just passively take the knowledge different authors convey to you. Try to really think about the ideas you read and have a conversation or debate with them. Figuring out what is not yet known about your topic is powerful. This gap in knowledge is a good area from which to generate research questions. Pay special attention to whether certain assumptions underpinning a conclusion should be re-examined, or whether scholars have significant disagreement about a subject.

Talk to professors and fellow students. If you have no clue how to generate a researchable question from academic literature, discuss your ideas with your professors. They can give you suggested readings and potential research directions, as well as fill you in on current debates within the field. Also, don’t forget your fellow students! Some students have started study groups to help formulate ideas for research questions. Students can review each other’s research questions to give comments and criticisms.

Put your research topic in the context of other theories. It is likely that your research topic has already been studied using certain theoretical approaches. (Theories are a way of organizing knowledge and explaining certain phenomena or events in the world.) Therefore, don’t be surprised if you come across a body of literature with similar arguments and theoretical approaches. You are always free to situate your research topic in relation to other theories to help you produce research questions. See our web pages on constructing arguments and positioning them relative to surrounding scholarly literatures.

Look at the end of review papers for suggestions. Many scholarly books and journal articles pose further research questions at the end of the books or review papers. Pay attention to these questions; they represent the thoughts of an experienced researcher about what still needs to be studied. Take them as guidelines for exploring your own research questions. Of course, you may wish to just absorb them as your research question if they fit your research interests well.

Look for interesting correlations between factors. From the preliminary reading that you do, pay attention to things that may be related. For example, suppose you are interested in how disease affects landscapes. As you do preliminary research, you find that in your landscape the rising rate of AIDS is concurrent with the declining area of crop planting. This initial finding will help you to frame a research question concerning the relationship between AIDS, crop planting, labor, and landscape transformation in the research site.

Return to Top of Page

Define the terms you use. You should consider carefully the meaning of every term you wish to use and define it somewhere in your writing. For example, a term like “globalization” could have a number of different meanings, depending on the topic and specialization of the author. A more specific term might be (for example) “increasing global interdependence of the financial industry.” Be specific, and try to write in language that your mother, father, siblings, or grandmother could understand.

Check your assumptions. As you develop your research ideas, consider carefully what assumptions you may be making. You should be able to verify your claims with appropriate primary or secondary sources. If you can’t verify a claim, consider whether it might be a bias or assumption. For example, suppose your research question is:

I am studying environmental legislation passed in the 1970’s…

because I want to know why and how such stringent laws were passed…

in order to help my reader understand how environmental legislation gets created and passed.

The first assumption to note here is that the 1970’s environmental laws were “stringent.” Were they? Can you justify this “stringency” and explain why it is interesting? What was unique about the 1970’s that would make this question interesting? The second assumption to note is that your research question will explain how environmental legislation gets created and passed. What if your research topic represents an odd situation and therefore says nothing about how environmental legislation is usually passed? Be careful of overstating the importance of your topic and making assumptions about what your narrative can tell us. A more precise question (one more conscious of its assumptions) might look like this:

I am studying environmental legislation passed in the 1970’s…

because I want to know the historical context that gave rise to this legislation…

in order to help my readers understand the historical significance of environmental legislation in the 1970’s.

Talk to professors and other experienced researchers. Ask for their help in figuring out your assumptions. Talking with your professors cannot be emphasized enough. Teaching you how to do research is part of their job! Most professors are delighted when a student is interested in their subject, and will be happy to talk with you about your ideas. They will also help you pick out your assumptions and biases, and help you articulate your research question in such a way as to acknowledge your biases without relying on them.

Continue to think about your time and budget constraints. You may have the best research idea ever, but if you need to be in northern Alaska to do it, you are going to need to find a plane ticket and some time. Good research can be done at home and in far away places. If you are lucky enough to have grant money or other money to help you travel, by all means, use it! But if you are not able to travel, consider what documents are available at your home institution, town, or state. Although the Internet has made interlibrary loan much easier, if you have to borrow everything from outside libraries it will slow down your research.

Be flexible! You never know what sort of surprises and interesting ideas you will encounter along the way. Keep a record of all interesting sources, documents, ideas, and questions. If something seems likely to be even marginally helpful or interesting, write it down. It is not likely that you will encounter it again.

Return to Top of Page

- Name one of your hobbies. Now try to connect this hobby to the environment. For example, if you are a musician, you may think about where the raw resources for your instrument come from. If you are an athlete, consider whether and how your sport has been played outdoors. If you like to knit, think about where the wool comes from.

- Use these thoughts to begin to generate some potential research questions. Always consider the question: What was the historical context that led to this situation? If your instrument is made of wood, where has the wood come from? Which wood is used, and why? How might the demand for instruments affect a landscape?

- If you are an athlete, has your game always been played outside? Has it been forced to respond to climatic conditions? Where do the materials for your sport come from?

- If you knit, where did the wool come from? How were the sheep raised, and how might this affect the landscape? How have people’s relationships with agriculture affected wool production?

- Do ask questions of your professors, colleagues, and friends. Ask questions about things you don’t understand, things you wish to debate, or new ideas and theories.

- Do plan ahead: make sure you are reading, thinking, and writing long before your assignment (whether paper or prospectus) is due.

- Do remember that generating a research question is an iterative process.

- Do talk to a librarian. They are very skilled at helping people with research, and they may be able to point you to new sources.

- Do schedule time just to think. Carve out time from your schedule during which you can sit and think about your research and do nothing else.

- Don’t plagiarize. Not only is it bad scholarship, it could result in you failing the class or being expelled. The effort you save is hardly worth the risk.

- Don’t rely solely on the Internet. The Internet is a useful tool, but at some point you will need to go to an actual library.

Return to Top of Page

Interesting Links and Works Consulted

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. The Craft of Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Mann, Thomas. The Oxford Guide to Library Research: How to Find Reliable Information Online and Offline. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2005.

Return to Top of Page

|